Words and photos by Sam Katovitch

The PSFS building is a building of many firsts. The first skyscraper in the International Style in Philadelphia and the United States, the first “modern skyscraper” in the US, and one of the first high-rises to be fitted with central air conditioning. It also happens to be the first Philadelphia building I fell in love with.

Some people have mixed feelings about the International Style, saying it can be too staid and abstract, and citing Le Corbusier and his sterile concrete and punched windows, but PSFS was designed early in the movement, before it entirely shook off the exuberance of Art Deco and Streamline Moderne. I had always seen pictures on social media of the view from the roof, and this summer I had a chance to go up there for a class on the history of Philadelphia’s architecture. The class was guided through the building by the facilities manager, who said of the ten or so classes he had given tours to, only our class and one other had actually been allowed on the roof.

A bit of background is needed. The PSFS tower was built in 1932, when the Philadelphia Savings Fund Society needed a home for its new headquarters and flagship bank. They brought in architects William Lescaze and George Howe to design an “ultra-modern” building, but ultimately what the board of directors meant was “ultra-practical,” and their comments on the actual external appearance of the building were minimal, leaving the design mostly up to Howe and Lescaze. Together, the architects designed most aspects of the building, from the overall massing to the light fixtures in the banking hall to the elevator panels and door handles – an example of the Bauhaus principle “gesamtkustwerk,” which translates to “complete artwork.” The idea that an architect could design all aspects of a building was something practiced by Frank Lloyd Wright , as well as Mies van der Rohe and the other Bauhaus greats, and it is a concept very precious to my own design philosophy – so much so that I have the word tattooed on my arm as a reminder.

Visiting the PSFS Building

The class met the facilities director in the lobby of the building, which is now a Loews Hotel. The ground floor of the building was originally designed to be rented, while the second floor was where the Philadelphia Savings Fund Society had its bank and offices. The ground floor is now a restaurant and the lobby for the hotel. We then went up the huge processional stair to the second floor, which was the banking hall of the Society before it closed and is now an event space for weddings and banquets. The facilities director told the class how he had a savings account with PSFS as a child, and fell in love with the building then, and how that steered him to end up on his career path.

Savings (left) and Wild Abandon (right)

Upright (left) & Spire (right)

From the second floor, we took the elevator to the 33rd – thus skipping over the intervening floors of offices-turned-hotel rooms – to where the original boardroom for the PSFS bank is maintained as a second event space. The space has been kept as original as possible, down to the ebony and Hudoke wood veneer on the walls, and the coat hooks for the board members. Originally, each hook had a list of all previous board members who had used it, but those plaques have since been removed. The views of the city are commanding, even though many more tall buildings have since been built around PSFS. Originally, the view would have been much less crowded during the days of the gentleman’s agreement that kept all skyscrapers below the height of William Penn’s hat. City hall stood clearly in the foreground while the skyscrapers west of it were silhouetted by the sinking sun as twilight began falling. Since the boardroom also wrapped around the building’s summit to the east, the view in that direction extended all the way to Camden and far into New Jersey across the Delaware River.

The class milled around and took photos for a while longer, then as we were gathering to go back downstairs, one of the other students asked if we could see the roof. The facilities director thought for a moment, then agreed. We were led up a small staircase, past the chains for blocking unwanted trespassers, and out onto the roof beneath that huge, iconic sign. We got onto the roof just as the sun was going down behind the buildings of Center City. As the lights flicked on in the buildings around us, we all gazed around, each of us processing our thoughts in our own way. Some of us went underneath the sign to look out at the other side of the view. Some peered over the parapets at the streetscape several hundred feet below. Others looked up at the radio tower which surmounts the building. I stepped back as far as I could, got out my widest-angle lens, and got as many photos as I could of that iconic PSFS sign. I had to lean backwards over the parapet wall with my camera pressed to my eye to get the entire sign within the frame. 12th street rushed along 450 feet below me, but I didn’t care. I just needed that one shot.

Sailing

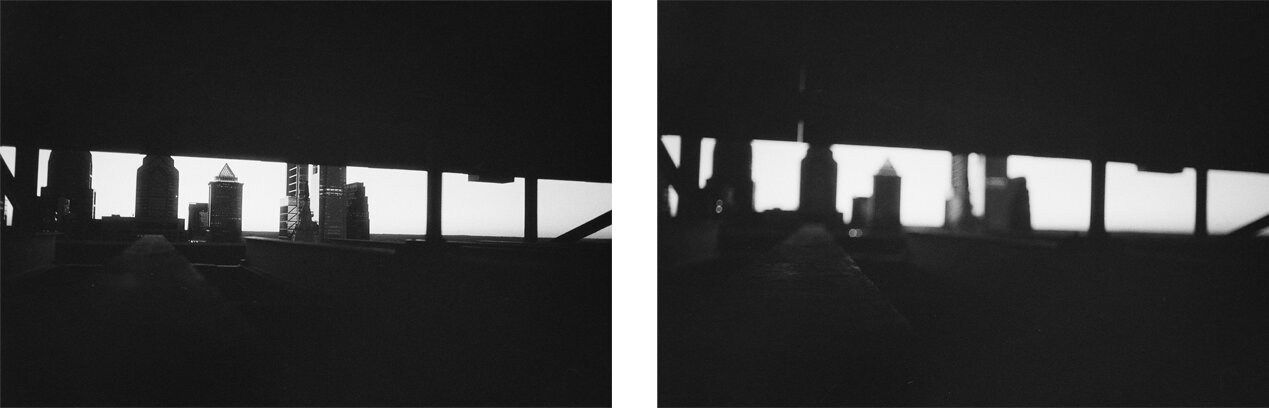

The other side of the building presented an equally spectacular photo opportunity. The huge sign is held aloft on a steel scaffold which is high enough off the roof to walk under. I rested my camera on one of the beams of the scaffold and took several alternate-focus shots of the skyline beyond. Focusing on the gritty surface of the steel near the lens gave the skyline an appealing blurriness, while focusing on the faraway buildings turned the steel beams into dark leading lines which pointed outward towards the silhouetted skyline.

Leading Lines (I & II)

All too soon, the Sun sank too far to get any more pictures, and while I would have loved to stay for another hour and take some long exposure shots, I left my tripod at home that day, and the facilities director ushered us back inside, since the roof is off-limits after dark. We made our way back through the echoing corridors and all piled into the elevators, chatting excitedly. I made a joke about getting the letters PSFS tattooed on me and the facilities director said he’d considered it himself.

On the way out of the building, the director told us one last story that really stuck with me. The building was built in the depths of the Great Depression, and the huge neon sign was seen by some as an excess, flaunting the wealth of the bank while the city floundered in poverty. But the sign stayed on, the director told us, because when it was turned off in response to those detractors, many more voices came back saying that the sign being on was a beacon of hope, showing that the bank was still up and running, and that one way or another, the city would get through those worst of times. That story really stuck with me because, ultimately, that should be one of the highest goals of architecture: to give hope and keep up spirits just by its mere presence, even in hard times. That should be the goal more often in modern architecture, as I think it’s something that has been lost since the more joyous style of Art Deco. After the International Style became the vogue, architecture lost much of its joy and humanity, and only regained some of it later, after the Malaise of the 70s had passed. PSFS stands still as a reminder that architecture can be both functional and joyous, and should stand as a beacon of neon light, even in the darkest of times.

Sam may be the only person you’ll ever meet with “gesamtkustwerk” tattooed on his arm.